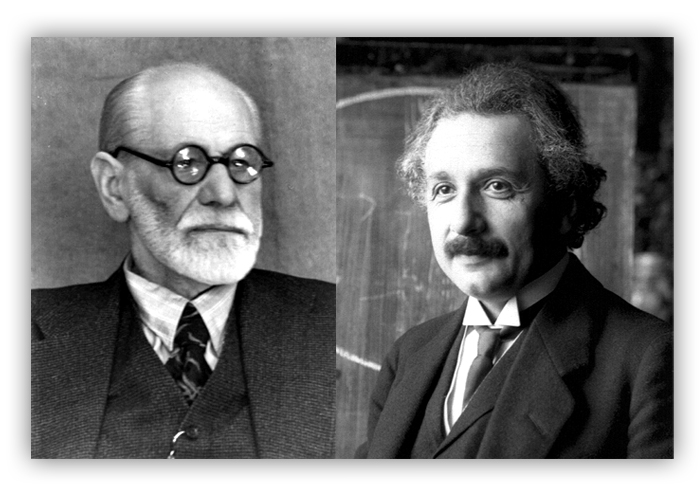

Albert Einstein And Sigmund Freud

The trouble of violence, perhaps the truthful root of all social ills, seems irresolvable. Yet, as about thoughtful people have realized after the wars of the twentieth century, the dangers human aggression pose have only increased exponentially along with globalization and technological development. And equally Albert Einstein recognized later on the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki—which he partly helped to engineer with the Manhattan Project—the aggressive potential of nations in state of war had reached mass suicidal levels.

Afterward Einstein's involvement in the creation of the diminutive bomb, he spent his life "working for disarmament and global government," writes psychologist Mark Leith, "anguished by his impossible, Faustian decision." Still, as we detect in letters Einstein wrote to Sigmund Freud in 1932, he had been advocating for a global solution to war long before the start of World War II. Einstein and Freud's correspondence took place under the auspices of the League of Nation'south newly-formed International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation, created to foster discussion between prominent public thinkers. Einstein enthusiastically chose Freud as his interlocutor.

In his first alphabetic character to the psychologist, he writes, "This is the problem: Is at that place any manner of delivering mankind from the menace of war?" Well before the diminutive historic period, Einstein alleges the urgency of the question is a affair of "common noesis"—that "with the accelerate of modern scientific discipline, this issue has come to mean a thing of life and expiry for Civilization equally nosotros know it."

Einstein reveals himself as a sort of Platonist in politics, endorsing The Republic'due south vision of rule by elite philosopher-kings. But unlike Socrates in that work, the physicist proposes not metropolis-states, only an entire world regime of intellectual elites, who hold sway over both religious leaders and the League of Nations. The upshot of such a polity, he writes, would be earth peace—the toll, likely, far too high for any globe leader to pay:

The quest of international security involves the unconditional surrender by every nation, in a certain measure out, of its freedom of action—its sovereignty that is to say—and it is clear across all doubt that no other road tin can lead to such security.

Einstein expresses his proposal in some sinister-sounding terms, asking how it might be possible for a "small clique to bend the will of the majority." His concluding question to Freud: "Is it possible to control human being'southward mental evolution so every bit to make him proof confronting the psychosis of hate and destructiveness?"

Freud's response to Einstein, dated September, 1932, sets up a fascinating dialectic betwixt the physicist's possibly dangerously naïve optimism and the psychologist's unsentimental appraisement of the human situation. Freud's mode of analysis tends toward what we would now phone call evolutionary psychology, or what he calls a "'mythology' of the instincts." He gives a generally speculative account of the prehistory of homo disharmonize, in which "a path was traced that led away from violence to law"—itself maintained by organized violence.

Freud makes explicit reference to aboriginal sources, writing of the "Panhellenic conception, the Greeks' sensation of superiority over their barbaric neighbors." This kind of proto-nationalism "was strong enough to humanize the methods of warfare." Similar the Hellenistic model, Freud proposes for individuals a course of humanization through education and what he calls "identification" with "whatever leads men to share of import interests," thus creating a "customs of feeling." These means, he grants, may lead to peace. "From our 'mythology' of the instincts," he writes, "we may easily deduce a formula for an indirect method of eliminating war."

And yet, Freud concludes with ambivalence and a great deal of skepticism virtually the elimination of violent instincts and war. He contrasts ancient Greek politics with "the Bolshevist conceptions" that propose a future end of war and which are likely "nether present weather condition, doomed to neglect." Referring to his theory of the competing binary instincts he calls Eros and Thanatos—roughly honey (or lust) and death drives—Freud arrives at what he calls a plausible "mythology" of human being:

The issue of these observations, as begetting on the subject in hand, is that in that location is no likelihood of our existence able to suppress humanity's aggressive tendencies. In some happy corners of the earth, they say, where nature brings forth abundantly any man desires, at that place flourish races whose lives go gently by; unknowing of aggression or constraint. This I can hardly credit; I would like further details about these happy folk.

Nonetheless, he says wearily and with more than a hint of resignation, "possibly our promise" that war will terminate in the near future, "is not chimerical." Freud's letter offers no like shooting fish in a barrel answers, and shies away from the kinds of idealistic political certainties of Einstein. For this, the physicist expressed gratitude, calling Freud'due south lengthy response "a truly classic reply…. We cannot know what may grow from such seed."

This exchange of letters, contends Humboldt State University philosophy professor John Powell, "has never been given the attention it deserves…. Past the fourth dimension the exchange between Einstein and Freud was published in 1933 under the title Why War?, Hitler, who was to bulldoze both men into exile, was already in power, and the messages never accomplished the wide circulation intended for them." Their correspondence is now no less relevant, and the questions they address no less urgent and vexing. You lot can read the complete exchange at professor Powell's site hither.

Related Content:

Albert Einstein Reads 'The Mutual Linguistic communication of Scientific discipline' (1941)

Listen as Albert Einstein Calls for Peace and Social Justice in 1945

The Famous Letter Where Freud Breaks His Relationship with Jung (1913)

Sigmund Freud Appears in Rare, Surviving Video & Audio Recorded During the 1930s

Josh Jones is a author and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Albert Einstein And Sigmund Freud,

Source: https://www.openculture.com/2015/09/albert-einstein-sigmund-freud-exchange-letters.html

Posted by: ferrarifichalfic.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Albert Einstein And Sigmund Freud"

Post a Comment